|

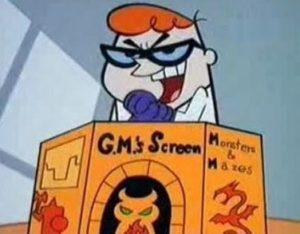

| The real mystery is how to get 6 adults to show up to one place at a given time |

But in fact, you should already be putting elements of mystery into your campaign.

Part of crafting a story (of which a mystery is a certain kind) is creating tension and excitement. Normally tension is created when two or more characters have conflicting goals, and in fantasy stories one of those characters is usually "the villain." In fact, nearly all RPGs have a "villain", simply because it's easier to introduce tension between the PCs and an NPC than between the PCs themselves. Fighting at the table is why people play monopoly or Mario Party, not D&D.

Excitement comes from two different sources. One is simply the players doing cool things and impressing their friends or affecting the world in cool ways. The system of D&D is built around this idea and you can generally figure out how to make people feel cool by reading DMing tips online.

The other source of excitement comes from exploration, discovery, and the unknown. If doing cool stuff lets the players affect the world, exploration gives them a world to affect. If pitting characters against each other creates tension, exploration gives those conflicts a stage upon which to perform, and stakes to be claimed.

And when it comes to the unknown, mysteries are a great way to pace a campaign.

Lore as Reward

|

| Re-lore-wd? Nope, doesn't work. |

There's not much to this campaign. We have tension, and opportunities to let the players show off their cool tricks. But there's little exploration. We basically can learn about the bad guy's plan, or maybe where the tower is or perhaps how to enter it. But that's so little, it's hard to see that level of exploration really holding the attention of a group of players for an entire campaign.

So how do we add more exploration? Well, let's add more world. Perhaps the trail is fraught with peril. Perhaps the gate to the tower is locked, and 5 gems must be obtained before the door can be opened. Perhaps an army lies within the walls of the tower. Perhaps the Bad Guy is just a front for the Real Bad Guy who is controlling him.

But imagine the players know all of this at the beginning of the campaign. Is that really exploration? Discovery? Excitement? Or is it just a series of boxes that have yet to be checked?

Now, as an aside, I know that some players love this kind of beer-and-pretzel gaming, where the point is to test your tactical knowledge and try to "win" each encounter. But we're talking about stories here.

In a well-paced campaign, the knowledge of these challenges becomes known to the players shortly before they have to overcome them. If the first thing the players must do is travel to the castle, they can immediately know the road is fraught with peril. But when do they know about the 5 gems? When they reach the gate?

Well, in a worst-case scenario, yes. Reaching the gate is how you ensure the players learn about the 5 gems. But if you think of this as part of a mystery, you can spread clues out in your campaign and treat them as a reward.

For example, you could have a player find one of the mysterious gems early in the campaign. You could tell them the legend of the five great beasts, each with their own gemstone. You could have different locks in early sessions that require five of something. You could even have them meet the architect of the tower and learn about the gate itself and the 5 gems needed to unlock it.

There are two important points here. First, most of these clues give only partial information. The gate is a major obstacle, so if the players can figure it out based on the partial information, they can work towards bypassing it sooner. Awesome! But again, we have a failsafe if they don't. They could find the architect and learn everything. Or if they miss the architect, they will eventually arrive at the gate and learn about the gems themselves.

The second point is the even more insidious one. The clues can be pretty obscure. Locks that require five of something? That's pretty hard to connect to the gemstones. But even if your players don't get your clue, the fact that you included these 5-locks will become another useful story element: foreshadowing.

So when you are putting together rewards for your players, you should consider giving them lore that relates to their goals. It could act as a clue, subtle foreshadowing, or even the final puzzle piece that lets them better face the upcoming challenge.

And of course, once they solve the mystery, you should let them face that obstacle as soon as possible. Otherwise you'll waste the excitement of the moment.

Solving the Mystery

After the mystery is solved, however, what happens next? Well, there has to be a bigger obstacle, and more lore leading up to it. And then a bigger one. Then a bigger one. And hopefully by then, your players are level 20 and you can stop the campaign. |

| Big enough to destroy your campaign |

This leads us to two important concepts: scope and focus.

Scope is about the size of the lore, but also the rate of change between pieces of lore. If you solve a mystery in the basement of a tavern, and the next mystery is about a shipment for the tavern that went missing, the scope of the lore is fairly small. If you go from killing rats to killing Gods, the scope of the lore is huge. This correlates to levels - going from level 1 to 2 requires a smaller jump in scope than going from level 5 to 11.

Focus is the limits of your lore. You could run a game where the players simply explore a single village, learning about the drama unfolding between its inhabitants and solving their problems. This would be small in scope. However, you'd also have to keep things low-level. In 5e, higher levels tend to go wild with magic in a way that would really break that kind of game. When you wanted to start a new campaign, you could just go to the next village over and build a whole new set of lore.

So once your players finish up an obstacle, you should already have an idea of the next obstacle, simply by virtue of knowing what level your characters will be when they get there and how far they will travel to find it. If the party just killed Ragnar the Orc King, and they are level 5, then your next obstacle should related to the fallout of Ragnar's deposition, and it should be a level 6 challenge.

Also, the obstacles you throw at players tend to be connected by some plot thread. Which means you can use an obstacle as lore leading to the next one. If the players learned about Ragnar's Lieutenant Mister Stabby, they could have learned that Mister Stabby is never far from Ragnar. Thus, Finding Mister Stabby could be a clue that Ragnar is nearby.

But sometimes the mystery gets too big. You find yourself with a mission that has the whole world as its stakes. What then?

Well, you don't have to build a brand new world. Instead, start things over in a new continent or city. Just because your last campaign was a world-spanning epic tale doesn't mean your new one has to be.

Alternatively, add a world-shaking event. Perhaps an old legend turns out to be true, and now the dead are returning to life! Perhaps a strange happening suddenly threatens the world, and the peace the last party achieved now hangs in the balance once more.

But my advice is try to keep it small. Keep things unexplored. Then, when the campaign ends, you can start a new mystery without too much trouble.

|

| Or, if you are a genius storyteller, ignore this advice. |

No comments:

Post a Comment